The Pathology of EEHV

Daniela Denk,MRCVS, Dr med vet, Dipl ECVP, International Zoo Veterinary Group

Jaime Landolfi, DVM, PhD, DACVP, Univ of Ill. Zoological Pathology Program

EEHV Gross pathology:

Gross lesions of fatal elephant hemorrhagic disease due to EEHV infection reflect the widespread damage to endothelial cells, resulting vascular leakage and hemorrhagic diathesis.

Though character, extent and severity of gross findings may vary depending on the EEHV strain involved, the time course of the disease and therapeutic measures, principal lesions include:

- Lingual cyanosis

- Widespread edema (may affect the trunk, head, neck, limbs and dependent abdomen, intestinal wall, mesentery and mesenteric root, omentum, and lungs)

- Pericardial effusion

- Cardiac petechial to ecchymotic hemorrhages

- Visceral petechiation (may affect a wide range of variable tissues)

The following additional findings have been recorded in EEHV-1, EEHV-3, EEHV-4 and EEHV-5 associated fatalities:

EEHV-1:

- Hepatomegaly (inconsistent)

- Oral, laryngeal, and large intestinal ulcers

- Intracranial and subcutaneous hemorrhages

- Hemorrhages throughout the stomach, small and large intestine

EEHV-3:

- Ascites

- Petechiae of intestinal serosa and ulceration of intestinal mucosa

- Hemorrhages within kidneys and urinary bladder

- Lymphadenopathy (reddening and edema)

EEHV-4:

- Facial swelling

- Hydrothorax

- Hemorrhages and ulceration along intestinal tract

- Testicular cyanosis

EEHV-5:

- Swelling of the eyelids and head

- Subcutaneous edema and petechiation

- Ascites

- Lymphadenopathy (reddening and swelling)

The following images depict some of the main gross findings in a severe case.

- a. Swelling of the trunk, head and eyelids with lingual swelling and cyanosis

- b. Swelling, cyanosis and petechiation of the tongue

- c. Widespread subepicardial and myocardial hemorrhages

- d. Edema and multifocal serosal hemorrhages body cavity

- e. Mesenteric edema and intestinal serosal hemorrhage

Images courtesy of Mr Jonathan Cracknell, Longleat Safari and Adventure Park, EEHV Advisory Group.

Edema, effusions and multiorgan hemorrhages, often with significant cardiac involvement, are likely to underlie the rapid circulatory shock and death.

A combination of above listed findings in susceptible animals should strongly suggest elephant hemorrhagic disease. Differential diagnoses include bacterial sepsis and coagulopathies (toxins, autoimmune mediated, parasitic), which should be considered for sampling purposes and supplementary testing.

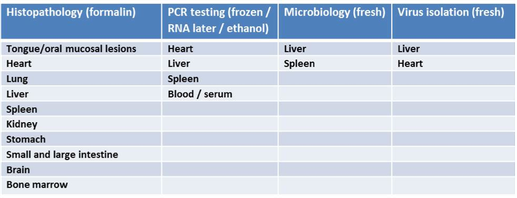

The table below outlines the recommendations for minimum tissue sampling of suspected EEHV fatalities.

Tissues for PCR testing should be retained and submitted to one of the reference laboratories (https://eehvinfo.org/members-area/testing-laboratories/) frozen. Where this is not possible, tissues can alternatively be fixed and submitted in RNA later or 95% ethanol. Please consult with the desired laboratory on samples/shipping.

To date, scientists have not been able to culture EEHV. For ongoing research, fresh liver and heart of fatal hemorrhagic disease cases or spleen obtained from other elephant necropsies including asymptomatic adults should be submitted to Gary Hayward, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

EEHV Histopathology:

As gross lesions suggestive of EEHV are not specific to the infection, histologic evaluation is essential to better characterize gross lesions and further confirm EEHV infection.

Histologic features of elephant hemorrhagic disease due to EEHV infection may include:

- Microhemorrhages with interstitial edema and low numbers of neutrophils, macrophages and/or lymphocytes

- Endothelial cell hypertrophy or necrosis

- Endothelial cell intranuclear inclusions. Inclusions may range from eosinophilic to amphophilic or basophilic and are typically smudged with variable margination of nuclear chromatin

- Vascular mural edema and fibrinoid degeneration

- Microthrombosis

Some variation in lesion distribution is noted for the different recognized strains of EEHV:

EEHV-1: Vascular lesions are predominantly detected in the heart, tongue, and liver and may be restricted to capillaries. Other reported histologic changes have included mild hepatocellular degeneration and oral/laryngeal mucosal ulceration or necrosis.

EEHV-3: Tissue tropism is broader including kidney, uvea, splenic capsule and alimentary tract as well as heart and liver. Affected vessels include capillaries, venules, small veins, arterioles, and small arteries.

EEHV-4: Alimentary, respiratory and cardiovascular systems have hemorrhage, edema, and mild inflammation.

EEHV-5: Broad distribution of vasculopathy noted with endothelial cell intranuclear inclusions in capillaries of heart, lung, liver, adrenal gland and oral mucosa. Inflammation and necrosis in the liver.

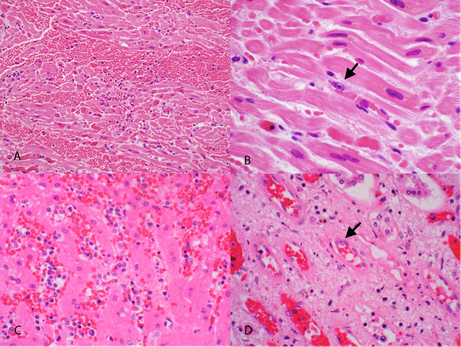

Photomicrographs of some characteristic EEHV histologic lesions:

- A. Myocardium with acute interstitial hemorrhage

- B. Endothelial cell of myocardial capillary containing herpesviral intranuclear inclusion (arrow)

- C. Acute renal interstitial hemorrhage

- D. Renal vascular endothelial cell with herpesviral intranuclear inclusion (arrow)

In all cases, histologic lesions are indicative of endothelial cell injury with resultant vasculopathy. The pathogenesis of endothelial cell damage has not yet been elucidated. Direct virus-mediated injury is considered the most likely mechanism; other hypotheses include induction of apoptosis, immune-mediated insult, and secondary damage associated with coagulopathy.

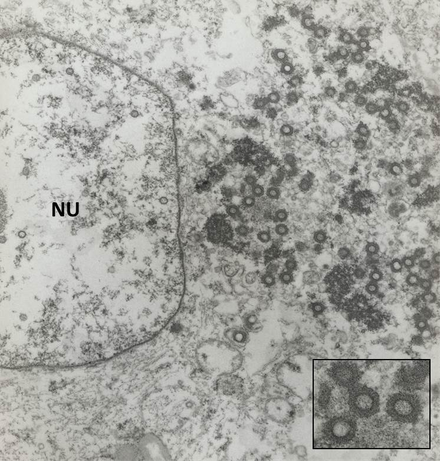

Ultrastructurally, endothelial cell intranuclear inclusions contain 70-90 nm, hexagonal herpesviral particles (inset). Enveloped particles may be visible budding from the nuclear membrane.

Image courtesy of Robert Nordhausen, California Animal Health and Food Safety Laboratory, Davis, California.

Thank you to Michael Garner of Northwest ZooPath, Timothy Walsh of the Smithsonian’s National Zoo, Jon Cracknell of Longleat Safari & Adventure Park and Gary Hayward of Johns Hopkins University for reviewing this prior to submission.

References:

- Wilkie GS, et al. 2014. First fatality associated with elephant endotheliotropic herpesvirus 5 in an Asian elephant: pathological findings and complete viral genome sequence. Sci Rep. 2014 Sep 9;4:6299

- Garner, M. M. et al. 2009. Clinico-pathologic features of fatal disease attributed to new variants of endotheliotropic herpesviruses in two Asian elephants (Elephas maximus). Vet. Pathol. 46, 97–104

- Richman, L. K. et al. 1999. Novel endotheliotropic herpesviruses fatal for Asian and African elephants. Science 283, 1171–1176

- Richman, L. K. et al. 2000. Clinical and pathological findings of a newly recognized disease of elephants caused by endotheliotropic herpesviruses. J. Wildl. Dis. 36, 1–12

- Sripiboon, S. et al. 2013. The occurrence of elephant endotheliotropic herpesvirus in captive Asian elephants (Elephas maximus): first case of EEHV4 in Asia. J. Zoo. Wildl. Med. 44, 100–104.